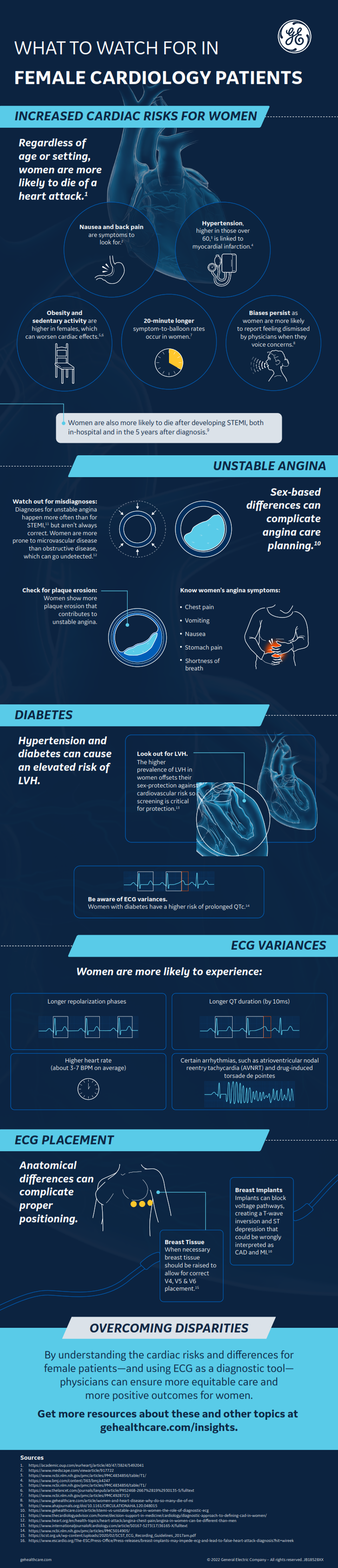

Sex-based disparities in diagnoses and outcomes are well known in many areas of cardiology, including in cases of acute MI and sudden cardiac death, but the underlying causes of these differences are still being interpreted and understood.

Diagnosing unstable angina in women and men,* compared to diagnosing ST-elevated myocardial infarction (STEMI), is one such area. Female patients are diagnosed more frequently with unstable angina than STEMI, and they also experience higher cardiac mortality than male patients, as Cardiology Advisor notes.1 Yet sometimes those diagnoses may be incorrect.

The reasons for these variances can be biological or cultural, requiring clinicians to take a multidimensional and comprehensive approach to diagnostics and treatment. Practitioners must also utilize tools such as ECG to inform care planning as quickly and thoroughly as possible for all patients.

Physiological Factors in Female Patients

Many sex-based differences in perceived anginal versus STEMI indicators derive from physiological manifestations. Importantly, the coronary artery diameter of a female patient is proportionally smaller than that of a male patient, according to the European Society of Cardiology (ESC).2

This structural variance should be understood in context with evidence that, compared to men, women experience fewer known incidences of plaque obstruction and rupture contributing to STEMI. Rather, women show more plaque erosion that contributes to unstable angina, as Cardiology Advisor observes. Autopsies have shown that a female patient's risk of developing obstructive disease is less prevalent until their seventies. Instead, as the American Heart Association reports, women are typically more prone to microvascular disease, which can go undetected.3

Some evidence has pointed to sex-based differences in angina symptoms as well. In addition to (or instead of) lingering and unprovoked chest pain, female patients may experience gastrointestinal signs, such as vomiting, nausea, or stomach pain, as well as shortness of breath. Cardiology Advisor adds that some research also points to a potential difference in pain perception as another conflating factor.

Even angiography doesn't show the whole picture, especially for female patients. According to a report in Clinical Medicine Insights: Cardiology, women who have undergone angiograms have received normal results even though they demonstrated other indicators of myocardial ischemia, either through intravascular ultrasound or lab testing for troponin.4 These oversights may be due to damage undetectable by angiography.

Cardiologists looking to high-sensitivity cardiac troponin test results to assess the potential for myocardial injury need to consider sex differences. The U.S. chest pain guidelines note that women in this situation are at risk for underdiagnosis, and stress that cardiac causes should always be considered. 5 They also highlight that there are sex-specific upper reference limits to consider when interpreting the test results.

There is robust evidence establishing that 99th percentiles are lower in women than in men and that use of these cutoffs improves the underdiagnosis of women, according to a paper in Circulation.6 Such sex-specific thresholds have been adopted by the Fourth Universal Definition of MI and are included on the labels of all high-sensitivity cardiac troponin assays cleared by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.7 Whether use of different thresholds for men and women ultimately improves clinical outcomes is an area of active research.

Gendered, Cultural Factors To Consider

Atop these possible biological causes, gendered and cultural factors can also complicate diagnostic decision-making.

The ESC suggests that diagnosing and treating obstructive CAD (which male patients are more likely to have than female patients) is the norm in cardiology practice, leaving a significant portion of female patients who have microvascular problems instead of obstructive disease underrepresented. These differences connect to the greater conversation of gender disparities in medical education, as well as the general practice of using men's symptoms as the baseline and considering women's symptoms and presentations atypical.

In addition, women tend to be managed differently after symptoms begin, as a study of ACS patients in PLoS One shows.8 According to the study, women were less likely to receive aspirin and other guideline-recommended medications and underwent angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) less frequently. In the STEMI subset, women had longer times to treatment, and in both the STEMI and non-STEMI (NSTEMI) cohorts, they had increased mortality compared to men.

Anecdotally, too, many women have expressed that their providers discount their concerns as anxiety or other non-cardiac problems, which can delay in-hospital care.

Cultural issues, particularly around underrepresentation of racial and ethnic groups, may also influence how women are treated for cardiovascular disease. A study of American Muslim women in Health Equity, for instance, showed that heightened vigilance against perceived and experienced discrimination was associated with greater alcohol use and a higher likelihood of being overweight.9 The authors say the findings "suggest countervailing forces may affect the health of American Muslim women," which surely makes managing their medical conditions more challenging.

Stay on top of cardiology trends and best practices by browsing our Diagnostic ECG Clinical Insights Center.

Using ECG To Inform Diagnostic Care Planning

If neither symptoms nor angiography are altogether reliable—and troponin's clinical utility continues to wane amid COVID-19—how can providers assess the risk of unstable angina versus STEMI for all patients equally? A 12-lead ECG is an excellent starting point as part of a broader toolkit that may include lab testing and advanced imaging.

While STEMI on ECG can be determined via ST-segment elevations in the anterior, inferior, or posterior views, discerning NSTEMI from unstable angina can be more challenging. As Healio describes, both diagnoses can come with certain abnormalities, such as depressions in the ST segment or inversions in the T wave.10

However, sometimes ECG may appear normal for both unstable angina and NSTEMI, which would require lab testing and regular ECG testing (every six to eight hours) for creatine kinase and, debatably, troponin. Cardiac biomarkers will rise with NSTEMI but not for unstable angina.

Making Fast and Accurate Diagnoses

Differences in cardiovascular structure and symptoms, combined with unintentional disparities in care, can muddy the diagnostic workup for patients with cardiac concerns, particularly female patients. These complications can have dire effects on patient outcomes, as STEMI, NSTEMI, and unstable angina all have different care pathways.

ECG may not be the only tool required to arrive at the right diagnosis, but it is easy to use, fast, inexpensive, and accessible at the point of care. Most importantly, it can help to rule out STEMI in the absence of visible ST elevation.

Together, these indicators can be lifesaving for women who would otherwise be vulnerable to poor outcomes.

*For the purposes of this article, we are referring to "women," "female," "men," and "male" as reported in the cited studies. Most research does not track current gender identity or gender assigned at birth.

References:

1. Mieres J. Diagnostic approach to defining CAD in women. TheCardiologyAdvisor.com. https://www.thecardiologyadvisor.com/home/decision-support-in-medicine/cardiology/diagnostic-approach-to-defining-cad-in-women/. Accessed September 13, 2022.

2. Maas AHEM. The clinical presentation of "angina pectoris" in women. ESCardio.org. https://www.escardio.org/Journals/E-Journal-of-Cardiology-Practice/Volume-15/The-clinical-presentation-of-angina-pectoris-in-women. Accessed September 13, 2022.

3. American Heart Association. Angina in women can be different than men. Heart.org. https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/heart-attack/angina-chest-pain/angina-in-women-can-be-different-than-men. Accessed September 13, 2022.

4. Graham G. Acute coronary syndromes in women: recent treatment trends and outcomes. Clinical Medicine Insights: Cardiology. February 2016; 10: 1-10. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4747299/

5. Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. November 2021; 78(22): e187-e285. https://www.jacc.org/doi/10.1016/j.jacc.2021.07.053

6. Sandoval Y, Apple FS, Mahler SA, et al. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin and the 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR guidelines for the evaluation and diagnosis of acute chest pain. Circulation. July 2022; 146: 569-581. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.059678

7. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). Circulation. August 2018; 138: e618-e651. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000617

8. Lee CY, Liu KT, Lu HT, et al. Sex and gender differences in presentation, treatment and outcomes in acute coronary syndrome, a 10-year study from a multi-ethnic Asian population: The Malaysian National Cardiovascular Disease Database—Acute Coronary Syndrome (NCVD ACS) registry. PLoS One. February 2021; 16(2): e0246474. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0246474

9. Budhwani H, Borgstede S, Palomares AL, et al. Behaviors and risks for cardiovascular disease among Muslim women in the United States. Health Equity. October 2018; 2(1): 264-271. https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/heq.2018.0050

10. Healio. Coronary artery disease – unstable angina/non-STEMI topic review. Healio.com. https://www.healio.com/cardiology/learn-the-heart/cardiology-review/topic-reviews/coronary-artery-disease-unstable-anginanstemi. Accessed September 13, 2022.

Statistic Callout