Today, Kate Annable’s daughter, Ruby, is an active 9-year-old who climbs the monkey bars and loves to entertain her family. But before Ruby was born, Kate and her husband, Aaron, received a diagnosis that made them question whether their daughter would even survive. The information helped doctors develop a plan for Ruby’s delivery and emergency care that gave her the best possible chance at a healthy life.

Kate had known that she wanted children since she was young. She and Aaron met growing up in Australia when Kate was 6 years old and were married by the time she was 21. But her first two pregnancies ended in miscarriages that were emotionally devastating. When Kate became pregnant with Ruby, she was understandably anxious about the outcome, but her confidence grew as she progressed toward full term.

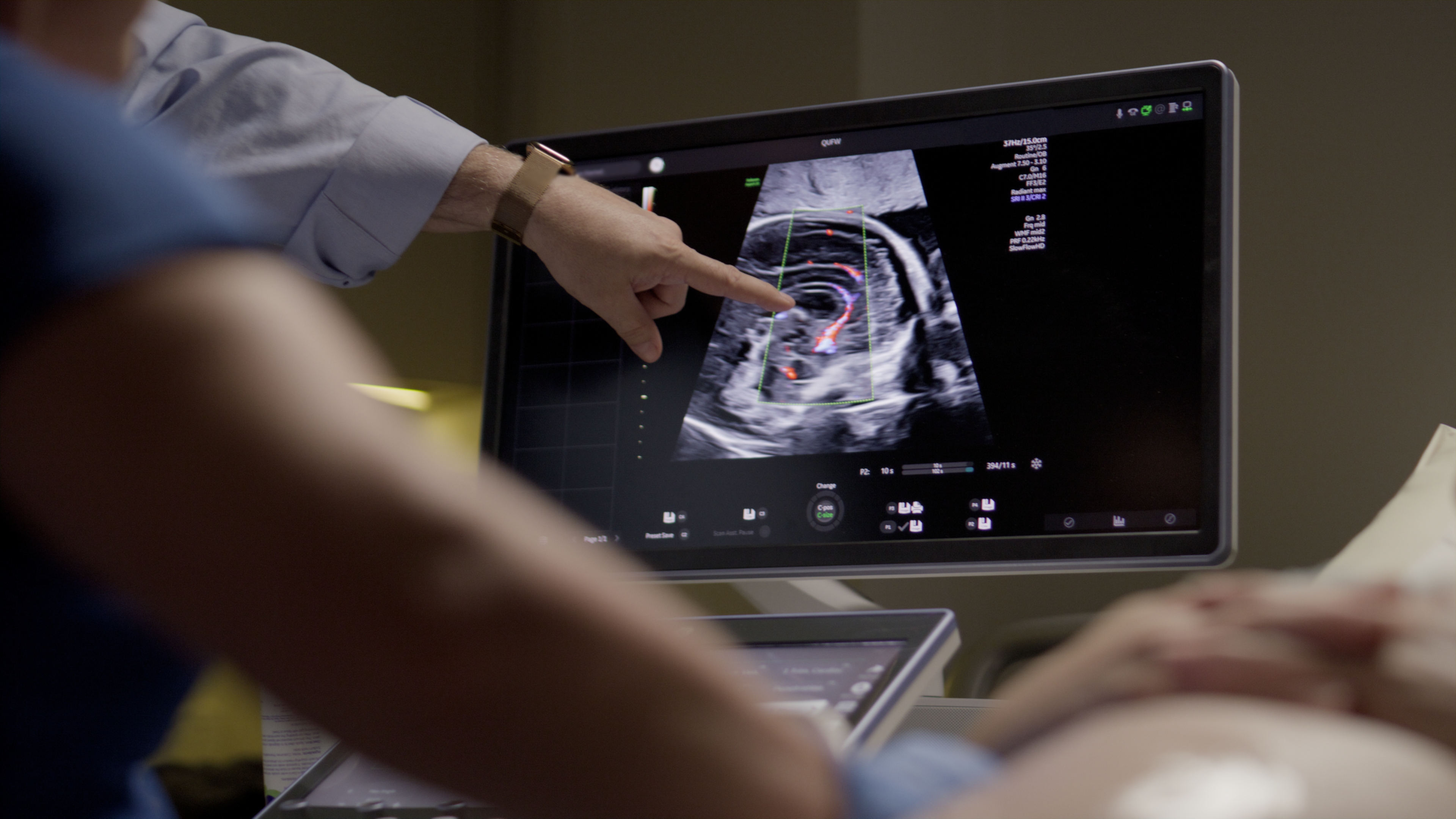

At 36 weeks, though, an ultrasound appointment, where she was scanned with a GE HealthCare Voluson Expert, completely changed her expectations. “They start at her feet and work their way up,” Kate recalls of the imaging process. “The sonographer just stops and stands in front of us and says, ‘We’re very concerned.’ What they had seen was what they termed ‘an event.’ From what they saw on that day, the damage was so significant, it was not going to be compatible with a full life.”

Ruby had experienced an intracerebral hemorrhage, a type of stroke characterized by bleeding into brain tissue. Fetal brain hemorrhage is a rare complication, occurring in perhaps 1 in 10,000 pregnancies. The doctors said they did not expect Ruby to live past age 2. Kate and Aaron were terrified. Kate remembers thinking, “My baby’s going to die.”

Stunned, they went home, where Kate unexpectedly went into labor around 4:30 a.m. Based on what they had learned from the ultrasound, her medical team already had created a plan for intervention.

“Making a diagnosis of a catastrophic intracerebral hemorrhage allowed us to change where Ruby delivered,” says Robert Cincotta, maternal fetal medicine specialist and obstetrician at Queensland Ultrasound for Women. “It allowed us to change how she delivered, where it was safer to deliver by cesarean section. And having the medical team available at the time of delivery allowed us to optimize the outcomes for Ruby.”

Robert Cincotta, maternal fetal medicine specialist and obstetrician at Queensland Ultrasound for Women

Immediately after her birth, Ruby was admitted to what is called a special care nursery in Australia. There, doctors began working to remove fluid from her brain. After three weeks, the fluid had cleared, and Ruby was released from the hospital to go home with her parents.

Ruby was diagnosed with cerebral palsy, a term used broadly to refer to disorders involving brain damage that affects movement. Because the hemorrhage was in the right side of her brain, it has primarily affected the left side of her body. Regular physical therapy has helped her increase her strength and coordination.

“The most important thing about early intervention is we have literally rewired Ruby’s brain,” Kate says. “Yes, Ruby’s brain damage is quite significant, but thanks to all of her therapy and everything that she’s worked so hard at daily, it’s why she’s able to do what she can do.”

Ruby

Ultrasound can help to diagnose medical crises like Ruby’s that occur late in pregnancy, but it also can do much more. Practitioners use ultrasound technology to detect structural problems in organs such as the brain and heart, as well as problems with a baby’s growth. Many of these problems can be diagnosed at a morphology scan that occurs at 20 weeks, when a fetus has developed sufficiently for medical practitioners to detect abnormalities. This ultrasound includes multiple images of different organs, as well as assessments of the placenta, umbilical cord, and amniotic fluid.

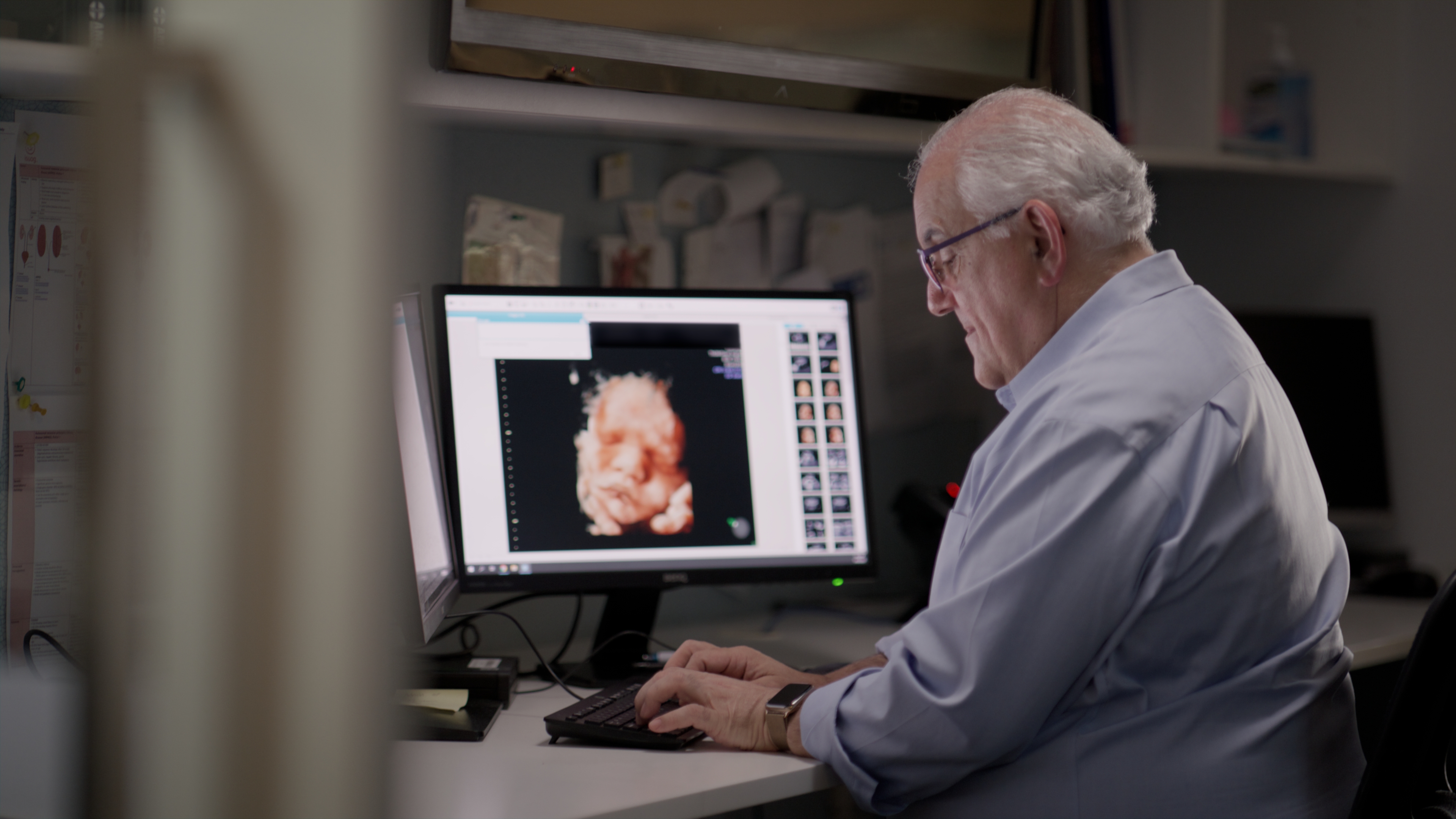

Improving technology, Cincotta says, now allows some problems to be detected much earlier, sometimes as early as 13 weeks. Abnormalities with organs such as the heart sometimes can be treated in utero. In situations like the Annables’, patients can be directed to deliver at a hospital that can provide an appropriate level of specialized care.

“The ultrasound technology has improved significantly over the past 10 to 15 years,” Cincotta says. “It is allowing us to image the structures much more clearly, and so we’re now able to pick up major structural problems at a much earlier stage and be much more confident about a diagnosis.”

Developments such as artificial intelligence and automation embedded in ultrasound technology also are improving the quality and consistency of imaging. AI can help with quality assurance by reducing the time it takes to perform measurements and confirming that all the required views of a fetus have been completed.

Because of such advances, detection rates for significant problems are likely to increase, Cincotta adds. “The goal is to always try and improve the outcome for the babies, if possible, and also for the families involved,” he says.

Kate Annable goes further: “I genuinely believe that the ultrasound saved Ruby’s life.”