Growing up in Indonesia, Edmond de Bie was regularly confronted by other boys looking to brawl. Edmond, a quiet boy who loved opera, was never prepared for the fight. On the other hand, Edward, his cantankerous identical twin brother, typically left the house with magazines stuffed under his jacket to soften whatever blows came his way, usually at his own instigation.

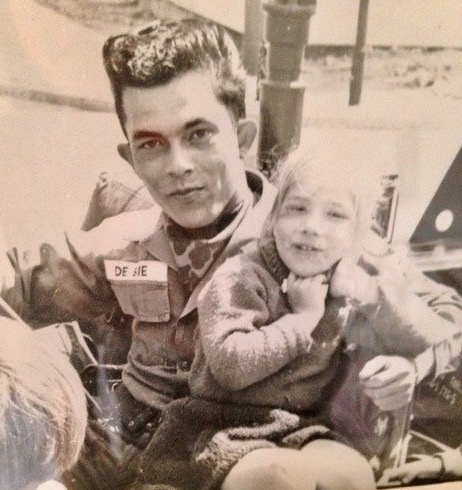

“My dad was a small South Asian man, but he was scrappy. He was always rumbling,” Connie Bailey says affectionately of her father, Edward de Bie, whose eventual struggle with Alzheimer’s disease led Connie to proactively plan for her own health and care should she ever face the disease.

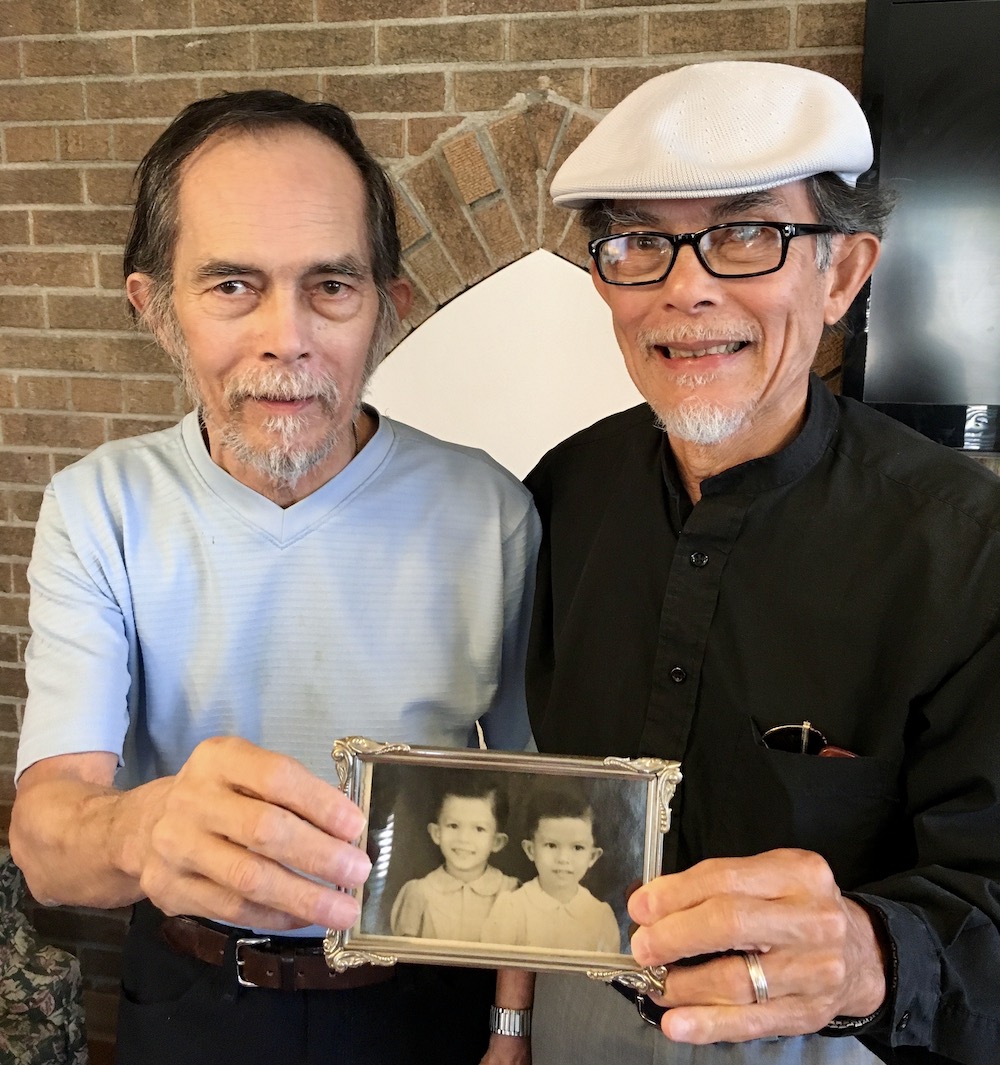

As twins, Edward and Edmond were very close. They immigrated to the United States together, worked as engineers at the same company in Wisconsin, and were neighbors when they retired with their wives to Florida. The two couples loved being together in the warm weather and sunshine. When Edward started showing signs of memory loss around 2013, his children back in Milwaukee attributed it to aging and being tired. Then, one day, he left for what was supposed to be a quick trip to the grocery store. Instead he was gone for hours. When Edward finally made it home, he admitted he’d gotten lost and couldn’t remember how to get back.

Edward and his twin brother, Edmond. Top: Edward and Connie.

“That’s when my brother, Eddie, flew down to Florida,” says Connie. “Dad was 73, and still so vital and healthy, you don’t think Alzheimer’s. But my brother called and said it wasn’t good, that Dad wasn’t well.”

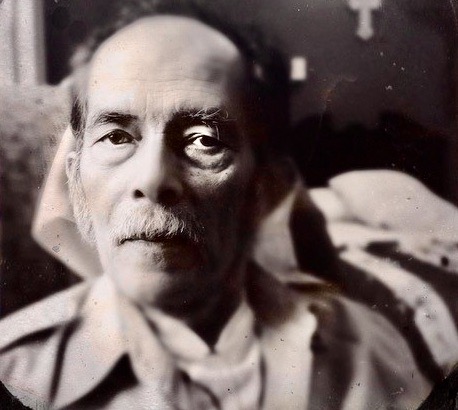

Connie and Eddie convinced Edward and their mom, Eileen, to return home. Back in Wisconsin, the family struggled to have Edward diagnosed and to cope with his steadily declining health. At the time, Connie had a toddler son to care for. Around the same time, Edward's twin, still in Florida, was himself diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

Amid all this, Connie and Eddie took turns sleeping on an air mattress to make sure their father didn’t wander outside overnight.

“In hindsight, it was obvious, but it took a long time to get a diagnosis, and when you’re in it, you don't really know what you’re dealing with. You’re just trying to get through and you want to hope for the best,” Connie says. “But the phone would ring and Dad would pick up the wrong end of the receiver.”

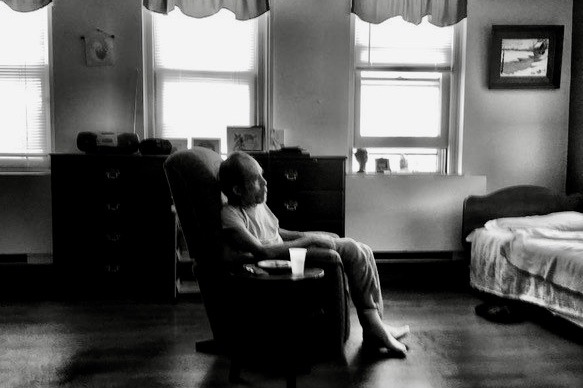

All too soon, Edward and Eileen had to move into a semi-assisted living center where trained professionals could care for him. When he was finally officially diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, rules required that Edward move into a memory care ward — alone.

Edward in his memory care facility

“When he was separated from my mom, that’s when he got absolutely worse,” Connie says. “My brother and I were there all the time because we couldn’t bear leaving him.”

Edward passed away in 2017, at age 77, not too long after the move to the Alzheimer’s floor, and Eileen followed him a few months later. Connie says her mother died of a broken heart. Edmond is still battling the disease and every day asks when he’s going to see his brother again. Edmond’s wife simply reminds him that Edward moved back to Milwaukee and will visit soon.

“That’s a big takeaway for me: Just tell them whatever the happiest and most positive outcome is, so they can be happy in that moment,” Connie says. “Give them that moment, because in two seconds they’ll forget and the confusion and anger will set back in.”

Edward in Germany while serving in the army

Things have slowly started normalizing for Connie over the past few years, and Eddie and his family followed a job opportunity to China, where they are thriving. Perhaps the biggest lesson Connie absorbed from her father’s illness is that she wants to take steps to protect her own health, for the sake of her son, who’s now 13. She’s taken out a long-term care insurance policy and signed up with Alzheimer’s specialists at the University of Wisconsin and is hoping to undergo assessments and create a baseline for herself for future comparison as she ages so doctors can detect any minute changes in her brain or cognitive function.

Connie says she is excited about a new drug that can potentially reduce amyloid plaques in the brain. In a large, 18-month study, treatment with the drug was proven to slow the progression of early Alzheimer’s. People with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) resulting from Alzheimer’s disease or with mild Alzheimer’s dementia are potential candidates.

This new therapy requires at least four magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans — taken before the start and again within the first six months of the therapy — to allow the clinician to evaluate potential adverse side effects of the treatment. Also, the presence of amyloid plaques in the brain, which the new therapy is targeting, need to be confirmed, which can be done using an amyloid PET scan to visualize the plaques. GE HealthCare solutions and technologies span across this new Alzheimer’s disease patient care pathway, from diagnosis to therapy planning and delivery to evaluation. Its suite of solutions can help clinicians see the finer details of the entire brain structure through improved efficiencies and enhanced image processing. It also helps clinicians achieve an early diagnosis of cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s and helps them visualize the progress of the disease.

Given her family history, Connie says she wants to explore every option and be prepared for any eventuality.

“If I’m doomed to be stricken with this, I don’t want my son to have to be put through what I was,” she says. “I’ve been a healthcare advocate for other people for 10 years, and now I’m advocating for my own future and health. It’s really not for me, though. I’m doing all this to protect my son.”

Discover more Alzheimer's stories