New information regarding COVID-19 continues to emerge daily. This content was based on the sources available at the time of writing.

Related Articles: Diagnostic ECG

Patients with COVID-19 have often presented with signs and symptoms that suggest significant cardiovascular disease, including acute chest pain or angina. In these patients, COVID-19-related ECG abnormalities, including ST-segment elevation (STE) and depression, can complicate the accurate diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome (ACS).

Given the importance of timely differentiation of myopericarditis due to COVID-19 from type 1 STEMI, a closer look at ECG changes, including reciprocal depression, is warranted.

Observed RSTD Patterns in Type 1 STEMI

ECG findings were first correlated with angiographic findings in patients presenting with STEMI in foundational studies from the 1980s. These studies identified ST depression occurring in leads remote from the infarct site, or so-called reciprocal ST-segment depression (RSTD).

Research published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology found that patients with a first acute STEMI showed RSTD present in 100% of inferior infarctions and 70% of anterior infarctions.1 Patients who have ST-segment depression or a combination of ST-segment depression and elevation have the highest incidence of cardiac death, re-infarction, and recurrent chest pain, as a study published in the Bratislava Medical Journal observes.2

Three different explanations for RSTD were proposed early on and have remained topics of controversy:

- RSTD is just an electrophysiological phenomenon in which the observed ST depression is the "rearview" or mirror image of the classic STE.

- RSTD is a product of myocardial necrosis or ischemia remote from the infarct site.

- RSTD is a result of the extension of the infarction beyond the index site.

A review published in the American Heart Journal suggests patients with RSTD are a heterogeneous group. In some, coexistent anterior ischemia is present,3 while in others, anterior RSTD is a passive reflection of inferior STE, sometimes reflecting either a larger infarct size or more extensive septal or posterolateral involvement. The review also notes that patients with posterolateral wall extension can be identified by the presence of reciprocal depression in the right precordial leads.

These foundational studies indicate that the presence and location of RSTD remain useful for accurate diagnosis of ACS in patients with chest pain, particularly in cases of inferior myocardial infarction.

Analyzing RSTD To Determine STE Etiology

Can RSTD help differentiate COVID-19 patients with STE due to STEMI from those with myopericarditis or other nonspecific causes of STE? Earlier studies on patients with STE—but without type 1 MI—may be useful for viewing COVID-19 patients with similar ECG patterns.

A study published prior to COVID-19 in the Scandinavian Cardiovascular Journal examined ECG changes in eighty-five patients with STEMI and ninety-four patients with nonischemic STE,4 all with acute chest pain. It yielded the following findings:

- Significant RSTD (defined as ≥0.025 mV in lead II) was noted in 40% of the anterior STEMI group members, but none of the nonischemic anterior STE group members (p<0.001).

- RSTD in aVR was not predictive of STEMI, as ST depression ≥0.025 mV in aVR was present in 80% of the nonischemic cases but only 30% of STEMI patients (p< 0.001).

- RSTD (ST depression ≥0.025 mV in lead I) in patients with inferior STE occurred in 83% of STEMI cases, but in none of the nonischemic cases (p<0 .001).

- Multivariate analysis showed RSTD "was the strongest independent predictor of ischemic STE etiology, whereas chest-lead PR depression and ST depression in aVR were associated with a nonischemic etiology," the researchers state.

RSTD has been described in nonspecific causes of STE, but it can usually be differentiated from ischemic STEMI. According to a paper published in the Journal of Electrocardiology, in early repolarization and acute pericarditis, reciprocal changes are commonly seen only in aVR.5 In patients with left ventricular hypertrophy, cardiomyopathy, and/or LBBB, the characteristic changes are STE in V1-V2 with ST depression in I, aVL, and V5-V6.

Characteristics of RSTD in COVID-19 Patients

But what have we learned about RSTD in COVID-19 patients who present with STE?

A case series of eighteen patients presenting with cardiac enzyme evidence for myocardial injury and STE, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, provides insights into the management of COVID-19 patients with potential acute coronary syndrome.6 Half of these patients underwent coronary angiography, and two-thirds of those studied invasively were believed to have had obstructive coronary disease.

The 12-lead ECG on all eighteen patients can be viewed in the supplementary appendix, along with still frames from the coronary angiograms. Five patients underwent percutaneous coronary intervention. After review of all clinical information, eight out of eighteen were believed to have MI (STEMI group) and ten out of eighteen to have "noncoronary" myocardial injury (NCMI group).

A review of the published ECGs for these patients shows RSTD present in seven of the eight STEMI patients (87.5%), versus only four of the ten (40%) NCMI patients.

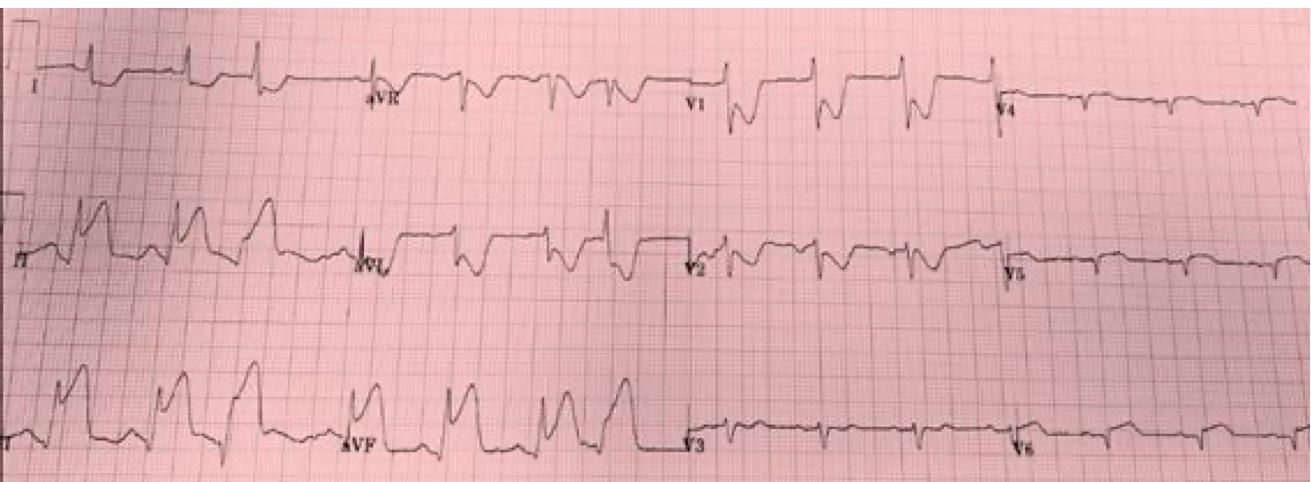

The ECG below was from a STEMI patient found to have 100% RCA at angiography. The RSTD is quite significant in both leads I and aVL, consistent with STEMI etiology.

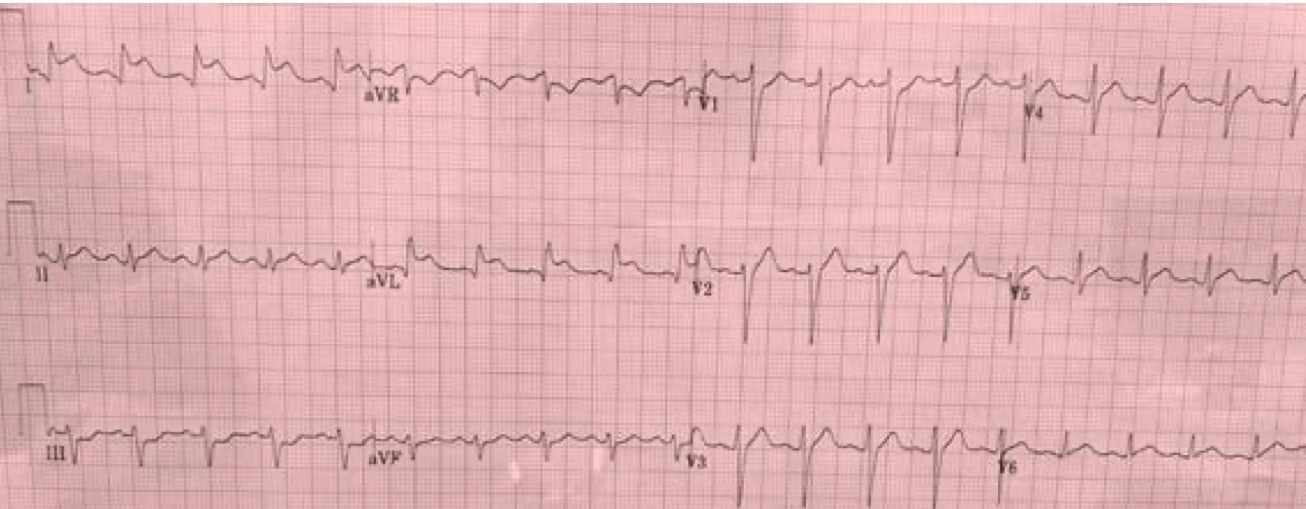

The following ECG is from a NCMI COVID-19 patient who underwent urgent catheterization on presentation with STE. The RSTD is prominent in lead aVR, with only subtle upward-sloping ST depression in leads III, aVF, and V1.

More recently, a study published in the American Journal of Emergency Medicine reviewed the ECG manifestations of COVID-19 and found that up to 90% of critically ill patients had at least one abnormality.7 The study provides ECGs from two patients with either anterior or inferior STEMI with focal STE accompanied by reciprocal ST-segment depression. The authors point out that "myocarditis and/or myopericarditis associated with COVID-19 infection can demonstrate ECG findings resembling occlusive AMI, such as focal ST segment elevation with reciprocal change."

ST depression has been observed in the setting of COVID-19, both among patients who ultimately met criteria for acute myocarditis and among those with STEMI, as a review published in the Indian Heart Journal notes.8

The Overall Value of RSTD

Differentiating type 1 plaque rupture STEMI from other myocardial complications of COVID-19 in patients with acute chest pain is essential. Informed ECG interpretation makes an important contribution to the rapid triage of patients to angiography when appropriate. The presence of RSTD in leads other than aVR is a helpful marker for patients who would benefit from early revascularization.

In this regard, it should be noted that UpToDate has recommended performing a 12-lead ECG at the time of entry into the hospital for patients in whom COVID-19 is suspected to allow for "documenting baseline QRS-T morphology should the patient develop signs/symptoms suggestive of myocarditis or an acute coronary syndrome," underscoring the importance of ECG for timely diagnostic insights.9

References:

1. Camara EJN, Chandra N, Ouyang P, et al. Reciprocal ST change in acute myocardial infarction: assessment by electrocardiography and echocardiography. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. August 1983; 2(2): 251-257. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0735109783801600

2. Schweitzer P, Keller S. The role of the initial 12-lead ECG in risk stratification of patients with acute coronary syndrome. Bratislava Medical Journal. 2001; 102(9): 406-411. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11763676/

3. Mirvis DM. Physiologic bases for anterior ST segment depression in patients with acute inferior wall myocardial infarction. American Heart Journal. November 1988; 116(5 Pt 1): 1308-1322. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3055909/

4. Lindow T, Pahlm O, Khoshnood A, et al. Electrocardiographic changes in the differentiation of ischemic and non-ischemic ST elevation. Scandinavian Cardiovascular Journal. December 2019; 54(2): 100-107. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14017431.2019.1705383

5. Birnbaum Y, Fiol M, Nikus K, et al. A counterpoint paper: comments on the electrocardiographic part of the 2018 fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction. Journal of Electrocardiology. April 2020; 60: 142-147. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0022073620301084

6. Bangalore S, Sharma A, Slotwiner A, et al. ST-segment elevation in patients with COVID-19 – a case series. New England Journal of Medicine. June 2020; 382: 2478-2480. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMc2009020

7. Long B, Brady WJ, Bridwell RE, et al. Electrocardiographic manifestations of COVID-19. American Journal of Emergency Medicine. March 2021; 41: 96-103. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0735675720311803

8. Mehraeen E, Seyed Alinaghi SA, Nowroozi A, et al. A systematic review of ECG findings in patients with COVID-19. Indian Heart Journal. November 2020; 72(6): 500-507. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S001948322030273X

9. Pinto DS. COVID-19: myocardial infarction and other coronary artery disease issues. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/covid-19-myocardial-infarction-and-other-coronary-artery-disease-issues. Accessed April 15, 2022.