Dr. Payal Kohli, MD, FACC

It was the middle of the night when I was suddenly awoken by a phone call about a young patient who was in the emergency room with a fever and an "abnormal ECG." Rubbing the sleep out of my eyes, I turned the lights on, reached for my laptop, and pulled up the ECG.

There was no reason to activate the cath lab, but it was definitely something that set off alarm bells in my head.

I had learned about Brugada Syndrome during my internal medicine residency and cardiology fellowship training, but clinically, it was somewhat rare to see Brugada syndrome or a Brugada pattern. The Brugada pattern, which occurs in asymptomatic individuals without any other clinical criteria, has an estimated prevalence of between 0.1% and 1%. Brugada Syndrome, which is marked by ECG changes and a history of sustained ventricular tachycardia or sudden cardiac death, is even rarer.

Looking for the Signs of Brugada Syndrome

It was also not surprising that the patient who was the subject of my midnight phone call was a young man, as the disorder has a two-to-nine-times higher predominance in men.1 Animal models suggest that testosterone may impact the outward potassium channel ion currents in the heart, but the male predominance continues to remain somewhat of a scientific mystery.2 It is also unclear why individuals with schizophrenia tend to have a Brugada pattern ECG more commonly than the general population. I wondered if the young patient I had been called about also had schizophrenia.

I glanced at his age: 32 years old. This was not a surprise, as most cases are diagnosed in adulthood, even though the condition follows autosomal dominance inheritance. Interestingly, there is variable penetrance of the condition in families, which made me wonder what this patient's parents' ECG looked like.

Some children who had a negative ajmaline drug challenge (without inducible Brugada pattern during childhood) have had the pattern unmasked after puberty.3 Event rates in the SABRUS registry (the largest international Brugada registry) tended to be low overall in the pediatric population. But when pediatric Brugada cases occur, they tend to be recurrent events and appear to be associated with fever.

Investigating a Brugada Patient's Cardiac History

I called back the emergency room attending physician right away. My first question was: "Has the patient ever had syncope, a ventricular tachyarrhythmia, or sudden cardiac arrest?" Thankfully, the answer was no. I inquired further about atrial fibrillation, since the risk of atrial arrhythmias is increased by 10-20% in patients with Brugada syndrome, which has also been associated with worsening disease severity and increased risk of ventricular fibrillation.4

I wondered if he had any nocturnal agonal respirations (a sign of aborted cardiac arrhythmia) and glanced at his potassium, which was at 4.2. Low serum potassium or high carbohydrate meals (which drive potassium into cells) are also known to increase risk of sudden unexpected death syndrome, which is thought to be in part due to Brugada syndrome.

Decoding Brugada Pattern on an ECG

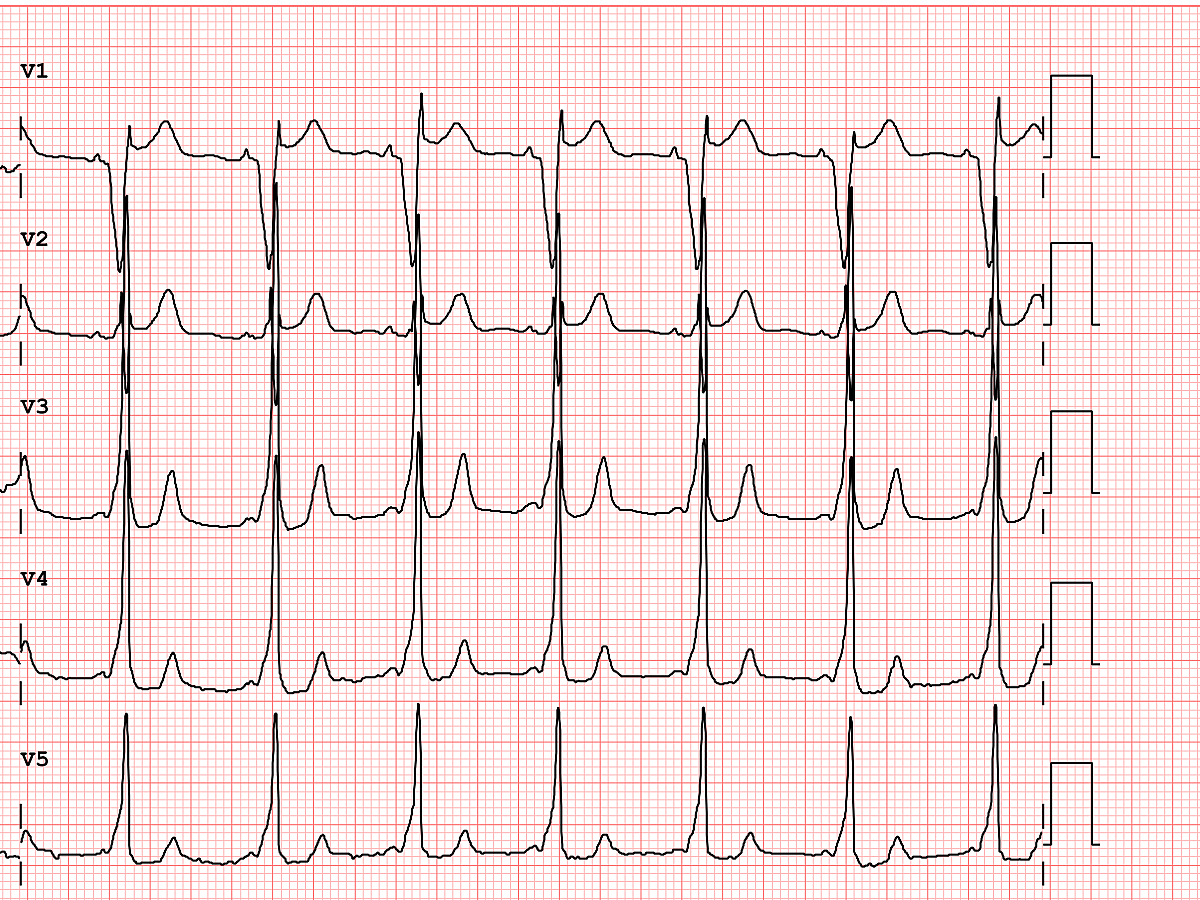

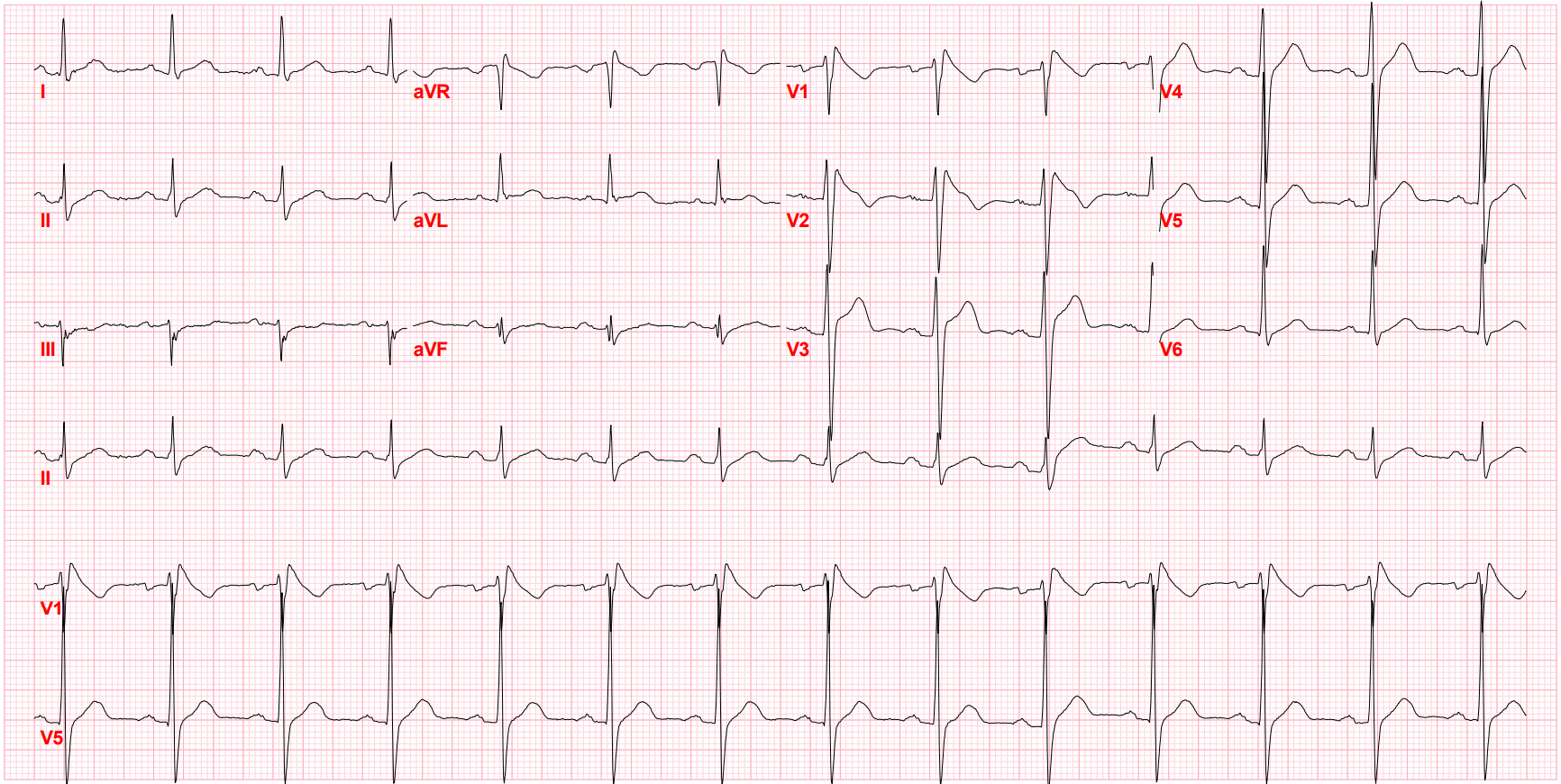

After I hung up the phone, I was too charged to go back to sleep. I stared at his ECG, probably the single most important screening tool for Brugada pattern or Brugada Syndrome. It showed the pseudo-right bundle branch block (without a widened S wave usually seen in RBBB) and persistent ST segment elevation in V1 and V2. His looked like a "saddle-back" Type 2 pattern, rather than the typical "coved" Type 1 pattern.

Brugada Pattern, Type I

Brugada Pattern, Type II

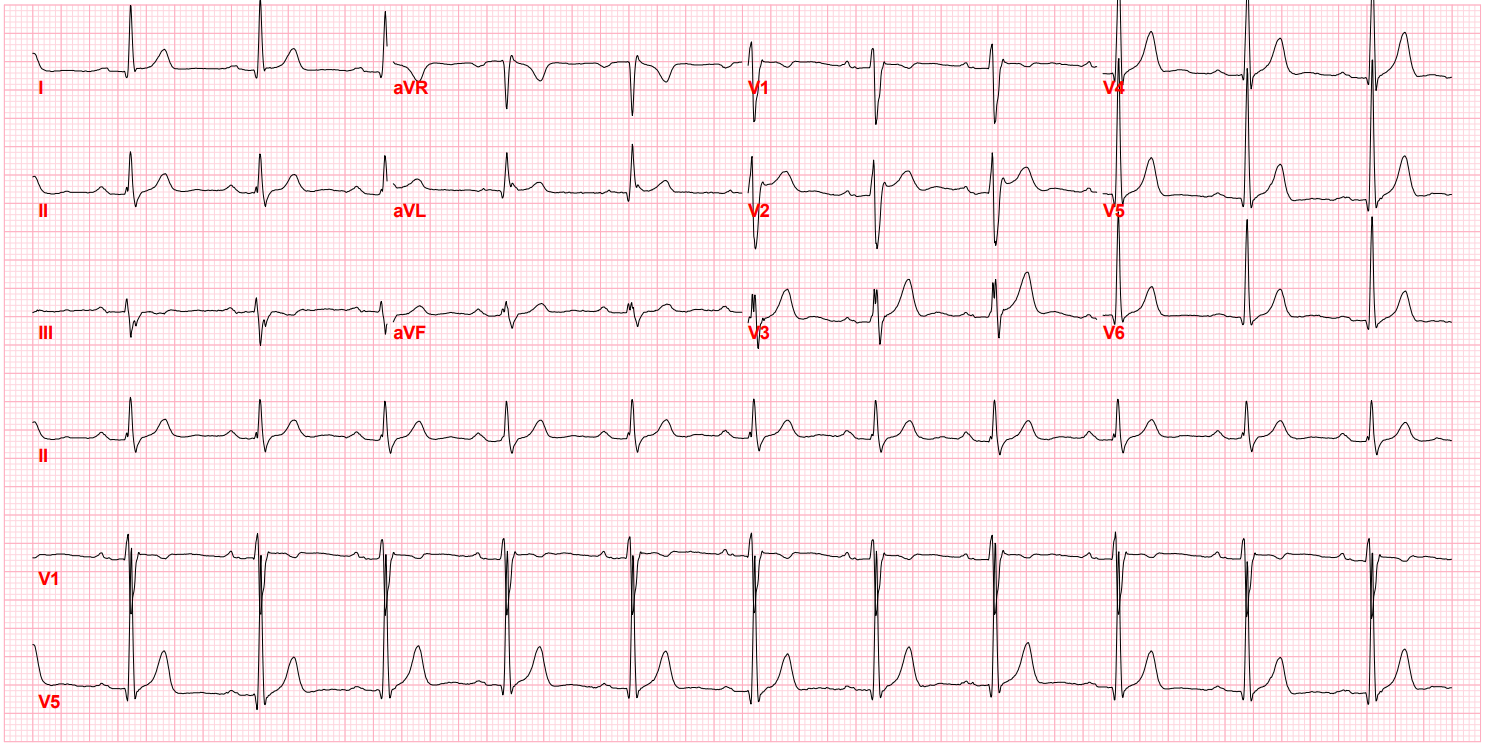

I remembered from fellowship training that moving the right precordial chest leads up the second or third intercostal space may be able to increase the sensitivity of detecting this pattern. In this case, there was no doubt about the diagnosis, but I had seen a case before where this maneuver was necessary. I knew that an infection and subsequent high fever had unmasked this young man's Brugada pattern ECG abnormality, as fever makes Brugada pattern ECG abnormalities twenty times more likely to manifest.5 Animal models have uncovered the mechanism: hyperthermia can impact sodium channel current function.

This patient had not taken any notable toxins, such as cocaine or alcohol. He did not take any medications, nor did he have any electrolyte abnormalities, such as severe hypo- or hyperkalemia.

Monitoring a Patient after a Brugada Incident

A few weeks went by, and the patient was referred to my office for further evaluation. His ECG in the office looked normal after his fever had resolved. Of course, I ruled out structural heart disease or myocardial ischemia with an echocardiogram and a stress test. His family history was unobtainable as he was adopted.

After the diagnostic tests results came back normal, I spoke with him about a drug challenge. I told him that if he had spontaneous Type 1 pattern, it would not require further testing, as the diagnosis would be confirmed. But in the setting of spontaneous Type 2 pattern, he should undergo a drug challenge with a sodium channel blocker to elicit a Type 1 ECG pattern. I explained how this is done with drugs such as flecainide, procainamide, or ajmaline with continuous ECG monitoring for 30 minutes, followed by a post-medication ECG at 90 minutes (if given IV) or up to 4 hours (if given PO). I also discussed the role of genetic testing and electrophysiologic testing with him, which may be appropriate to risk-stratify patients if there are inducible arrhythmias present.

To learn more about the power of the ECG in today's clinical landscape, browse our Diagnostic ECG Clinical Insights Center.

ECG serves a critical role in the diagnosis of Brugada pattern. It also has prognostic value, as an S wave in lead 1 >= 0.1 mV and >= 40 msec is a strong predictor of sudden death.6 The negative predictive value of this finding is quite high. It also can be helpful to obtain a signal-averaged ECG to identify patients at risk of future arrhythmic events.7

After my patient's EP study showed no inducible type 1 ECG pattern, I told him that his risk of sudden cardiac death was low (although his family history was unknown), so no ICD was indicated. I also advised him to talk with his known first-degree relatives about getting screened. I counseled my young patient to avoid any toxins that may increase his risk of ventricular arrhythmias, and he agreed to genetic testing. Although the condition is rare, I knew that identification of this Brugada pattern on his ECG would help us minimize possible triggers for ventricular arrhythmias, and it may have helped to save the young man's life.

References:

-

Shimizu W Tomaselli G, Tracy C. HRS/EHRA/APHRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of patients with inherited primary arrhythmia syndromes. Heart Rhythm Journal. December 1, 2013. https://www.heartrhythmjournal.com/article/S1547-5271(13)00552-3/fulltext.

-

Bai CX, Kurokawa J, Masaji Tamagawa M, et al. Nontranscriptional regulation of cardiac repolarization currents by testosterone. Circulation. 2005;112:1701–1710 https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.523217.

-

Conte G, Asmundis Cd, Giuseppe Ciconte G. Follow-up from childhood to adulthood of individuals with family history of Brugada Syndrome and normal electrocardiograms. JAMA. 2014;312(19):2039-2041. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/1935112.

-

Bordachar P, Reuter S, GarrigueIncidence S, et al. Incidence, clinical implications and prognosis of atrial arrhythmias in brugada syndrome. European Heart Journal. 2004;25(10):879-84. doi.org/10.1016/j.ehj.2004.01.004.

-

Adler A, Topaz G, Heller K, et al. Fever-induced Brugada pattern: how common is it and what does it mean? Heart Rhythm. 2013;10(9):1375-1382. doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.07.030.

-

Calò L, Giustetto C, Martino A, et al. A new electrocardiographic marker of sudden death in Brugada Syndrome: the S-wave in lead I. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2016;67(12):1427-1440. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.01.024.

-

Adler A, Rosso R, Chorin E, et al. Risk stratification in Brugada syndrome: clinical characteristics, electrocardiographic parameters, and auxiliary testing. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13(1): 299-310. doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.08.038.

Dr. Payal Kohli, MD, FACC is a top graduate of MIT and Harvard Medical School (magna cum laude) and, as a practicing noninvasive cardiologist, is the managing partner of Cherry Creek Heart in Denver, Colorado.

The opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints of GE Healthcare. The author is a paid consultant for GE Healthcare and was compensated for creation of this article.