In western Colombia — surrounded by towering mountains, an active volcano, and lush green coffee plants — lies the picturesque city of Manizales. In addition to being the heart of Colombian coffee production, the small community is also the hometown of Jorge Uribe and his father, mother, brother, and two sisters.

“My father was a civil engineer — he helped design the roads throughout the city — but we also had a farm, cultivating coffee, cattle, and plantains,” shares Jorge. “I went to school like any kid and, to be honest, I wasn’t deprived of things, but our community lacked certain opportunities. I could easily have gone on to follow in my father’s footsteps, but I wanted to do something that had no future in Colombia — I wanted to study the practical application of physics.”

Manizales, Colombia. Photo courtesy of Jorge Uribe

Jorge recalls sitting in class in high school and learning the basics about atoms, how they expel energy from the nucleus in the form of a particle or ray, and how that energy can become radioactive.

“I had no idea what radiation was, but my teacher handed me a book on the topic that piqued my interest. I was curious about all the good applications it has and thought, ‘This is awesome,’” he explains. “I knew someday I would like to work on something like this — to develop something good with it — but it was such a distant idea. There was no way I could connect that aspiration with sitting in a small corner room in a developing country’s coffee-growing region.”

Jorge went on to study physics at Universidad de los Andes, in Bogotá, and subsequently pursued a PhD in experimental particle physics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

“I never wanted to be stuck in front of a chalkboard or writing highly academic science papers. My pursuit of a PhD was to increase my physics knowledge to the point where I could get my hands dirty and build something that had more direct applications.”

Jorge left his hometown to pursue his dream, but that didn’t come without questioning his direction. When he was in grad school, the Nevado del Ruiz volcano erupted. Fortunately, Jorge’s hometown, Manizales, wasn’t directly hit — though it suffered damage to all of its major connecting bridges. For a month, the only way in and out of the city was by airlift.

The other side of the mountain wasn’t so lucky. Entire communities were buried in 10 to 20 feet of deep, mud-like debris. People didn’t have time to evacuate their homes, and thousands were killed. The devastation was heartbreaking — one pilot reported discovering that an entire town had completely disappeared during a routine flight.

A community covered in debris after the Nevado del Ruiz volcano eruption in 1985. Credit: Google Images

“That whole event shook me,” Jorge says. “I kept thinking: ‘I have all these privileges; I’m working in this university; I’m studying this very deep, complicated science; and now I see people being pulled out of the mud very close to where I grew up.’ And I asked: ‘Where should I be?’”

The answer came quickly: “I felt so far away from where the problems were and questioned whether I should go back, but then I realized that I had a purpose and I needed to continue chasing it. I had been given so many opportunities, I needed to keep pursuing them.”

Two years later, Jorge would experience another tragedy: the loss of his 60-year-old father.

“He had been diagnosed with polyps and lived with them for years, but the symptoms kept getting worse and worse. Finally they decided to do exploratory surgery, only to realize that cancer had spread all throughout his colon. They told my mother there was nothing they could do. He passed away six months later.”

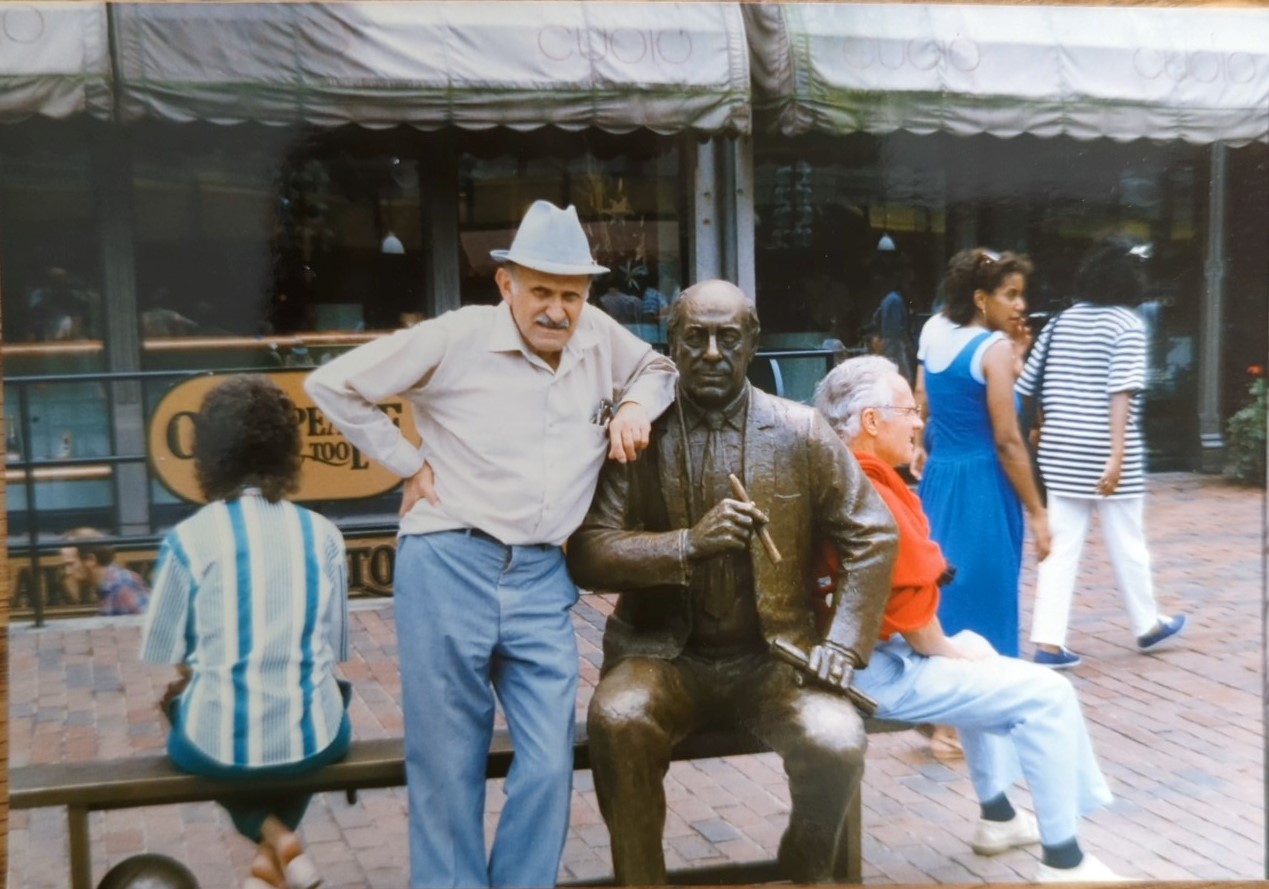

The last photo taken of Jorge’s father, as they explored downtown Boston only eight months before he passed. Photo courtesy of Jorge Uribe

Jorge says his father never had a PET scan. “We don’t have that kind of imaging equipment in the region. And while I won’t claim that experience as my incentive to get into developing PET systems, it did make me realize that I knew the science required to build that technology.”

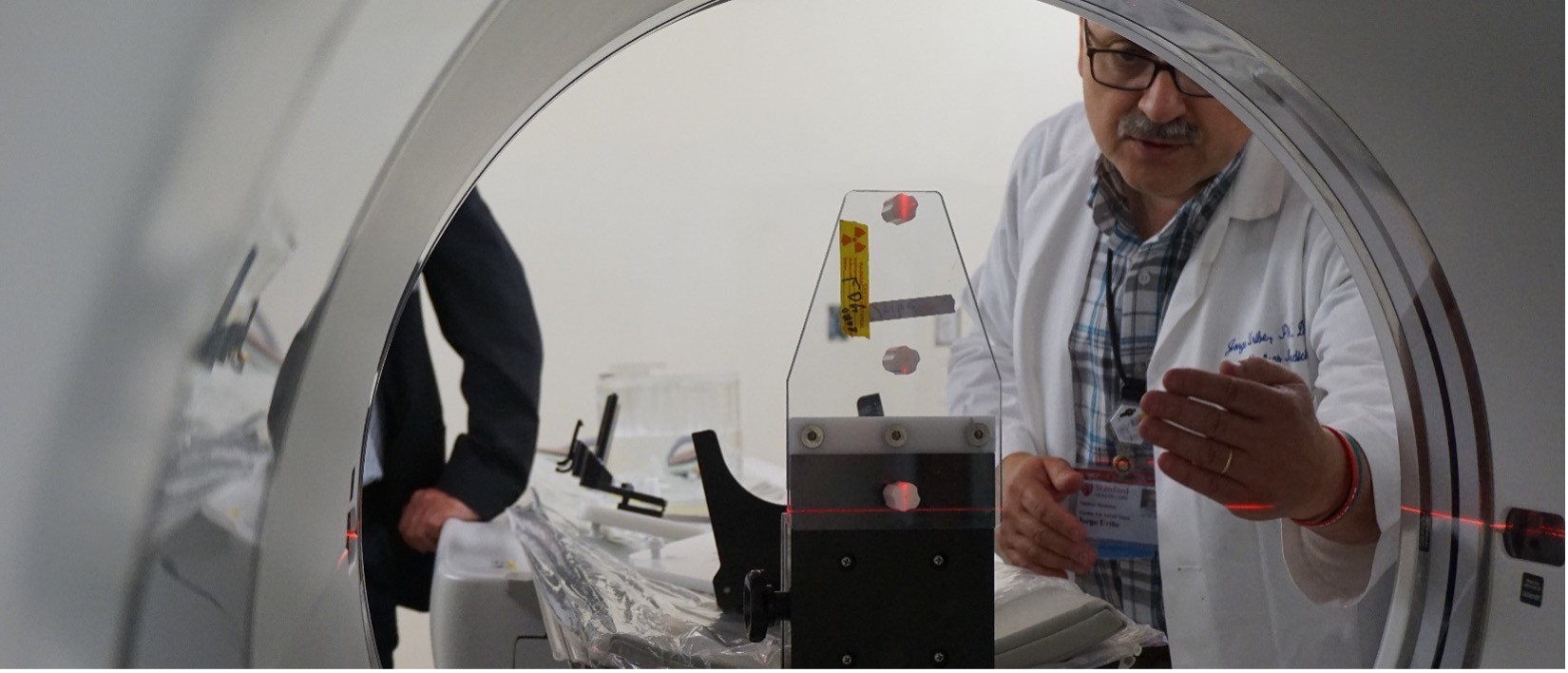

Upon completing his PhD, Jorge earned a postdoctoral position with MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, where he worked for 11 years applying physics to develop detector technology for PET imaging. In 2004 he joined the GE Healthcare team to help advance PET/CT technology, a type of imaging often used in oncology, which could have helped better diagnose and offer treatment options for his father.

“I joined GE with the hope of building a scanner and platform that could have image quality equal to today’s top-of-the-line scanners, but for community hospitals in the developed world and for smaller places in the developing world.”

A year later, Jorge’s mother-in-law was feeling ill, but the nearest physicians could only utilize X-ray images, since the nearest PET scanner was an expensive 8-hour flight away in the United States. Like his father, she also died at the age of 60, but from liver cancer — another outcome that might have been prevented, or certainly managed better, if a better diagnosis had been available with a simple PET scan.

Since then, Jorge has dedicated his career to developing PET/CT scanners — including the Discovery 610/710, Discovery MI, Discovery MI DR, and Discovery IQ — collectively helping to improve clinical outcomes for hundreds of thousands of patients all around the world.

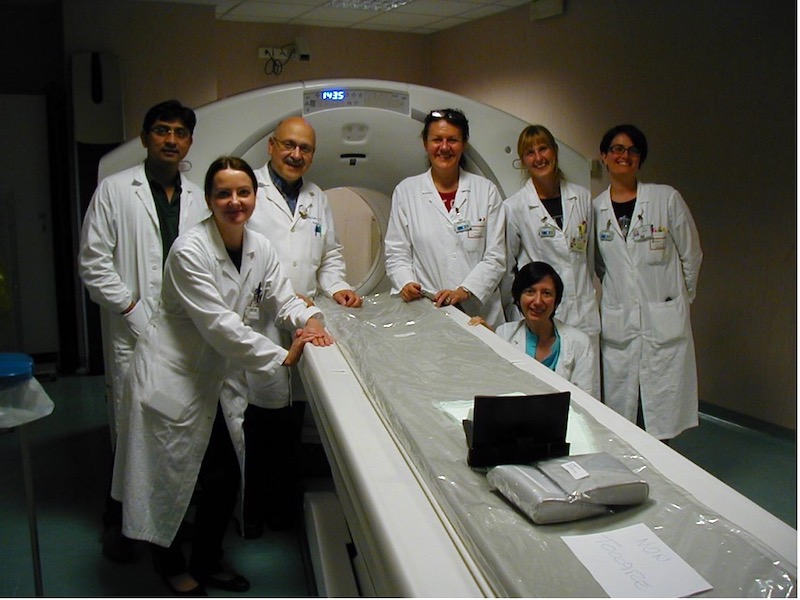

Jorge (third from left) with a team in Monza, Italy, after the installation of GE Healthcare’s Discovery IQ. Photo courtesy of Jorge Uribe

A few months ago, Jorge’s aunt shared an ad from the local paper. It was an ad promoting the county hospital’s fundraiser for the region’s first PET/CT system.

The ad promoting a fundraiser for the first PET/CT system near Jorge’s hometown. Photo courtesy of Jorge Uribe

“Seeing the ad made the system’s availability that much more personal,” he says. “I immediately started looking into who I could speak with at the hospital and learned that the facility’s president is an old neighbor in Manizales.”

“I’m excited to reconnect with her in the coming months to discuss whether the systems I have poured my heart into are the right fit, but I hope they are. It would certainly bring everything full circle.”

Whether or not a GE system is delivered to his local hospital, Jorge’s mentor and manager, Floris Jansen, has already sent him a note to let him know: “You can put a checkmark next to your mission to deliver this technology to smaller communities.”

–––––

For more information on GE’s latest scanners developed by Jorge and GE Healthcare’s team of engineers, visit gehealthcare.com.

Also watch this short film, inspired by the journey shared by Jorge and so many engineers around the world who are helping to solve human challenges with human hands.