Cindy Milgram wasn’t expecting anything unusual from her annual physical in August 2021. She was 47 years old and healthy, had no family history of heart problems, and was feeling fine. When the doctor detected something that sounded like a heart murmur, she thought it might be an anomaly because of “white coat” nerves. But when the sound came up again during a second check at the end of the appointment, the doctor decided to order an echocardiogram, out of what she told Cindy was “an abundance of caution.”

Cindy went in for her echocardiogram. Before she even got home, she had a call from the cardiologist’s office telling her that the doctor wanted to see her the next day. “It was not a question,” she remembers. “The doctor will see you tomorrow, you are his last patient of the day, and he will wait to talk with you.”

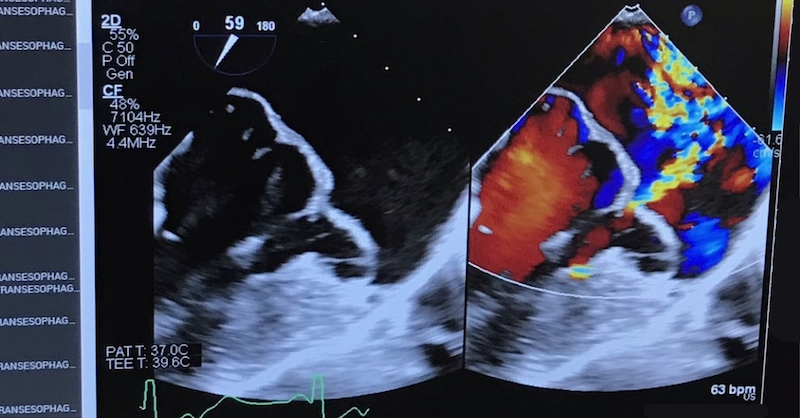

After listening to her heart for himself, the cardiologist confirmed that the heart murmur was in fact the sound of a leaking mitral valve. He decided she needed a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE), an internal procedure that uses sound waves to get a better look at the heart. The procedure required her to be sedated, so he sent her to a hospital near her home in suburban Milwaukee. That afternoon, Cindy received a phone call from the cardiologist, who told her that her condition was worse than he had thought — her left ventricle was enlarged, and he wanted her to meet with a cardiothoracic surgeon as soon as possible, which she did one week later. The cardiothoracic surgeon told her he would have to repair or possibly replace the mitral valve in her heart. Cindy was not convinced she needed surgery at all, because she felt fine, so the surgeon told her she could wait and be monitored every six months until she was symptomatic.

“Wait,” Cindy remembers thinking. “I’m going in to get a repair because I’m young and healthy, but then I get a new valve for the rest of my life because the repair may not hold? It was just overwhelming.” She decided to seek a second opinion at another local hospital. The cardiothoracic surgeon there told her he did mitral valve repairs every day and had a 95% success rate; he also suggested doing the surgery soon. But she wasn’t impressed by this recital of statistics. “I didn’t have the confidence that he saw me and [really] knew my story.”

Cindy decided to take matters into her own hands. She searched for the best mitral valve repair surgeons in the country and came up with three candidates: one in Chicago, one in Cleveland, and one in New York. She was prepared to visit them all.

The first was a cardiothoracic surgeon in Chicago whose stats were even better than those of the second surgeon: 5,000 surgeries, with a 98.2% success rate. But that wasn’t what impressed Cindy. What impressed her was that he interacted with her like she was a human being.

“He listened,” she says. “I felt like he heard what I was saying. He made every response personal, like he read my chart. It wasn’t like he was coming in like, ‘I’ve done 5,000 of these.’ It was like, ‘I’m talking to Cindy Milgram, who’s 47 years old, asymptomatic, and who is in shock by this diagnosis.’”

That sense of empathy and humanity was what Cindy had felt was missing from her conversations with other doctors, and it was the reason she decided to trust him to do the surgery.

Cindy’s experience is not uncommon among patients — or among doctors. A new study, Reimagining Better Health 2023, commissioned by GE HealthCare to help the healthcare industry add context and insights to better define industry challenges, recently surveyed 5,500 patients and patient advocates and 2,000 clinicians in eight countries to amplify their personal perspectives. Just 60% of the respondents — both patients and clinicians — said they still had the highest level of trust in their country’s healthcare system.

While healthcare has attempted to be more personal and accessible, the study revealed a system that has become disconnected from the very people it serves. Many patients, like Cindy, believe that they’re not being heard or seen as human beings: Only 42% of the patients agreed that “clinicians empathize with my personal situation and how it affects my treatment.” And many clinicians feel they’re not getting the chance to serve patients the way they had originally hoped when they entered the profession: Only 53% said they felt valued and supported by healthcare leaders and administrators, and 42% were considering leaving the field altogether.

The study showed that healthcare systems all over the world are broken. But Karen Becker, nurse practitioner and clinical development director at GE HealthCare, found some hope in it as well.

“As a clinician, what was most surprising for me was that there was consensus between patients and clinicians,” Becker says. “They’re experiencing the same challenges, and the things they want are the same.” That makes her optimistic that patients and clinicians will be able to come together and talk through ways to improve healthcare.

“It can be done,” she says. “It will take a long time. The challenge is that the model that is going to start being effective doesn’t exist today. But we can start to explore.”

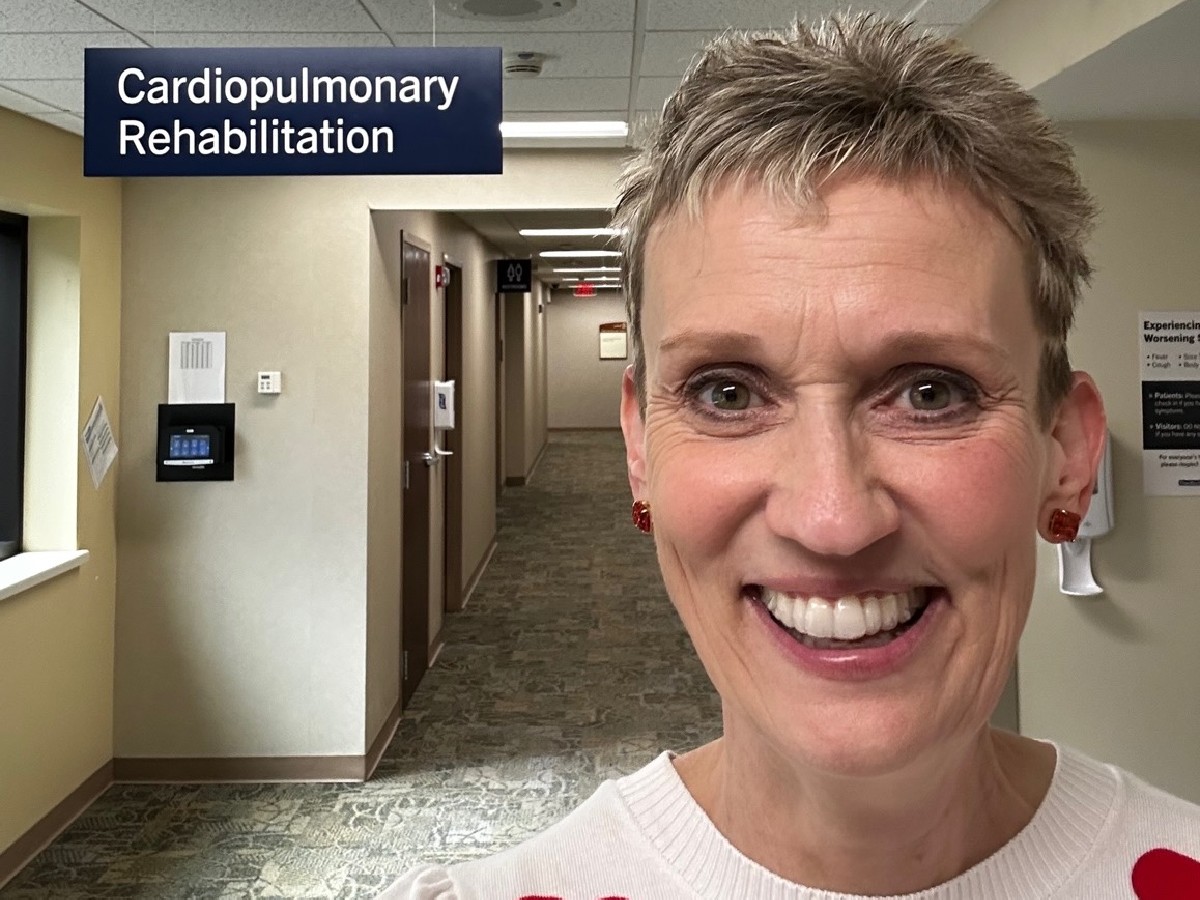

Whatever changes come about will happen partly because of people like Cindy. After her surgery — which was successful — Cindy realized that her story could help other women. Now she’s a certified WomenHeart Champion, a Mayo Clinic-trained patient advocate, who educates, supports and advocates for women living with or at risk for heart disease, both at local and national levels. She works with the Red Cross of Wisconsin and the American Heart Association and talks to other women her age about cardiac and preventive healthcare and encourages them to speak up and ask questions as she did. Because of Cindy’s personal journey, a local Wisconsin health system where she received mental health support following cardiac rehab partnered with a local health psychology program — like what patients going through cancer treatment have — to support women throughout their cardiac care journey.

“When I meet other women and tell my heart story, they are surprised that I asked questions of my doctors and wanted answers I could understand. You only get one heart, and I wanted to understand my diagnosis and treatment, since I had a life that I wanted to get back to living. Doctors are humans, too, and can make mistakes. I needed to trust the person doing my surgery, as he was going to save my life.”

Explore the full findings from GE HealthCare’s recent Reimagining Better Health study.