From the time he was a newborn, the older son of Sandra Sanchez Fahrlender and Bob Fahrlender struggled with his health. (He asked that his name be withheld to protect his privacy.) Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) kept him from sleeping for more than 45 minutes at a time. He had many ear infections and delays in speech and hearing. Before age 2, he had several surgeries on his ears, and doctors recommended removing his tonsils and adenoids. At 3 years old he contracted pneumonia and his lung collapsed, leading to a harrowing hospital stay.

At 4, the boy began passing out. He would stop breathing and go into convulsions. More than once, Sandra and Bob had to perform CPR while waiting for the ambulance to arrive.

As their son grew older, episodes of vertigo, fainting, and migraines became more frequent. Neuropsychological testing led to possible diagnoses, such as ADHD or autism, but despite studies performed by specialists in neurology, ENT, pulmonology, and cardiology, doctors remained uncertain about the underlying cause.

“We would chase individual problems,” Bob says, “but then it would turn into another problem. Every time a new symptom emerged and another caregiver was involved, it was like starting over.”

Still, their son loved to learn and excelled in school when he was well enough to attend. However, he missed so many days of class that his parents eventually had to homeschool him.

By the time he finished middle school, his health seemed to stabilize. In eighth grade, he attended a small private school, where he competed in four sports and participated in band, music, and theater. He also made the president’s honor roll.

But as he entered high school, wanting to feel “normal,” their son asked to play football. Though the game at his school was closer to flag football than tackle, Sandra and Bob were still apprehensive. The third day into football camp, he collapsed. In the months that followed, he was fainting four or five times a week and suffering such intense vertigo that he was sometimes unable to walk. Again the Fahrlenders sought help from doctors in several states.

He was bedridden for almost a year. “We were losing hope, because we didn’t have anywhere else to go,” Sandra says. The family contacted homeopathic doctors, hired professionals to search for mold in their home, and tested their son for Lyme disease. “We were so desperate. If they had told us to stand on our heads, we would have done it,” Sandra says.

After a week at Barrow Neurological Institute at Phoenix Children’s Hospital, doctors ruled out a neurological cause for his symptoms. There were still no clear answers.

Finally, a couple they knew mentioned that their own son had been experiencing major health problems until he had a pacemaker implanted. On their recommendation, the Fahrlenders, who live in New Mexico, took their son to a pediatric cardiologist in Albuquerque. Through additional testing, she found a small anomaly in his electrocardiogram, which records the electrical signals from the heart. She asked to perform an echocardiogram using a GE Healthcare cardiovascular ultrasound system, which uses sound waves to produce images of the heart. The teen had had several previous echocardiograms, so, while the family remained optimistic, they weren’t expecting to learn much.

The Diagnosis

Sandra will never forget the moment the doctor shared her findings. The whole family was waiting together: Sandra and Bob and their two sons. They were planning to go to a museum after the appointment.

“She comes back in and says, ‘Well, guys, your son has a hole in his heart,’” Sandra recalls. “It just felt like they sucked the air out of the room.” The doctor estimated that he had a 2-millimeter hole — called an atrial septal defect — between the upper left and right chambers of his heart. The doctor explained how a congenital heart defect might cause some of their son’s symptoms but probably was not the root cause. The doctor told them that a hole in the heart is relatively common, and that she could perform a simple 30-minute procedure to close it.

“We were just standing there shocked,” Sandra says. “Fifteen years of going down rabbit holes. No rest for our son at all.”

Congenital heart defects are the most common birth defect in newborns, affecting 1 in 110 babies. Yet they are often missed. Undiagnosed atrial septal defects like the one in the Fahrlenders’ son can damage a person’s heart and lungs, shortening life. Symptoms can include everything from allergies and asthma in young children to shortness of breath, heart palpitations, and fatigue. Congenital heart defects are about 50 times more common than childhood cancer.

After much research, they decided to move forward. The elective procedure was supposed to be brief, but it turned into an all-day operation involving several specialists and surgeons, using GE Healthcare interventional image-guided systems to find and repair the anomaly. The hole in their son’s heart was not 2 millimeters, but 10 millimeters.

Imagine a hole more than half the width of a dime in a structure the size of your hand. That’s what their son had been struggling with his whole life as his body and brain battled to get enough oxygen.

The morning after the surgery, Sandra’s son called to her from his hospital bed: “Mom!”

“Are you OK?” she asked.

His cheeks were rosy and his lips were bright pink. He had always been pale before that day.

“My fingertips are tingling,” he said.

“Oxygen is making its way to the tips of your fingers,” she told him. “That’s a good thing.”

So began years of recovery for a boy who had never known what it was like to feel healthy. He negotiated with the pediatric cardiologist to return to school in person, where he participated in Model United Nations, earned a place in the National Honor Society, and aced the SATs. For his senior capstone project, he produced his own music album. He went snowboarding throughout New Mexico and Colorado. He graduated at the top of his class and was accepted to several leading universities in the United States and Canada.

That doesn’t mean the journey has been smooth. The years of illness have taken an emotional toll on the entire family. Both the parents and their son, who is now 19, continue to learn about how having a congenital heart defect can be associated with anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Parents and siblings often need to recover psychologically, too.

After completing high school, Sandra and Bob’s son asked for a gap year before starting college. They have been traveling together to places like Olympia National Park in Washington state and New York City — trips they were never able to enjoy when their son was sick.

Helping Other Families Heal

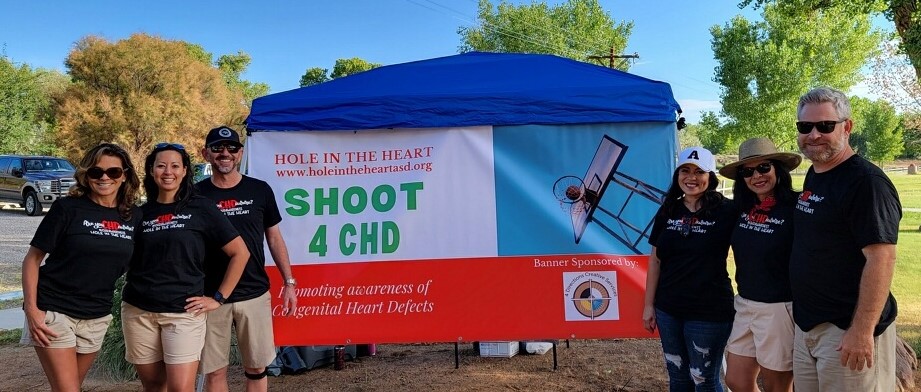

As the Fahrlenders shared their story on social media, they found other families enduring the same saga: a lack of knowledge and gaps in the continuity of care. So they founded a nonprofit organization called Hole in the Heart.

The organization has three goals: to raise awareness of congenital heart defects, to create partnerships between healthcare providers, and to advocate for best practices in diagnosing and treating congenital heart defects. Hole in the Heart is part of the GE Foundation matching employee gifts program. In just a few years, it has helped thousands of families with knowledge and resources.

“If we can help other families be diagnosed sooner — if they don’t have to go through what we went through — we consider it worth our efforts,” Sandra says.

Hole in the Heart is working with the American Academy of Pediatrics and the New Mexico Activities Association to include heart screenings as part of every child’s annual sports physical. The organization is collaborating with the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center’s Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) to create a telementoring program about congenital heart defects. Hole in the Heart is seeking experts in congenital heart defects to help build curriculum and create partnerships with primary care providers. Other initiatives are working to bring additional knowledge, training, specialists, and diagnostic equipment to underserved areas.

The odyssey to bring their son back to health inspired another change in Bob’s life. For more than a decade, he had worked in the healthcare device industry, helping to build several diagnostic imaging labs, mostly cath labs used in cardiology. After seeing how GE Healthcare products were used to diagnose and treat his son, he began working for GE Healthcare the next year after the surgery. Now he is a commercial executive supporting customers. “I wanted to work for the company that helped my family,” he says. “That’s my why.”

To learn more about Hole in the Heart, please visit their website, holeintheheartasd.org.